The Math of PUBG -- What is Average?

Am I Doing This Right?

While playing PUBG with a friend, I began to wonder: How am I doing this round? Of course I can compare my own performance to past games, but how do I stack up against players I am facing right now? Do I have a higher score than most, or less?

To put it more mathematically: At any given point in a round, what is the average score of the remaining players?

Playing the Game

For those not familiar with Player Unknown’s Batllegrounds (or PUBG), it’s an arena-style video game where 100 players fight each other until only one player remains. There is no structure to the fighting – everyone is dropped onto an island and forced inward over time, so players run into each other somewhat randomly (I’m greatly simplifying here). This makes determining scores difficult, since there is a wide range of possibilities.

Consider one case: Player B eliminates player A, so the average score is (1/99). Then, player C eliminates player B, making the average (1/98). If this continues, the average would incrementally increase until the very end, when there would be exactly one player with a score of 1. In this case, the average at any time is just 1 divided by the number of remaining players.

The very opposite scenario would be one player eliminating all the rest. Player A eliminates B, making the average (1/99). Then A eliminates C, making the average (2/98). The number would increase steadily until only player A remained with a score of 99. Here, the running average is the number of eliminated players divided by the remaining players.

Naturally, reality would to fall somewhere in between. I personally imagined the average acting like an exponential function, raising up by one every time the number of remaining players was cut in half, ending with one player averaging 6 or 7 points.

Creating a Simulation

Since the players’ scores aren’t open for everyone to see, I had to settle for making a crude simulation of a PUBG game in Python and testing my idea. The setup is simple:

import numpy as np

def simple_sim():

# Create an empty list to store averages over time

averages = list()

# Create list of integers representing players' scores

players = np.zeros(100)

while len(players) > 1:

# Pick 2 different players at random

winner, loser = np.random.choice(xrange(len(players)), size=2, replace=False)

# Increment winner's count, remove loser from players list

players[winner] += 1

players = np.delete(players, loser)

# Add new average score to averages array

averages.append(np.average(players))

# Return the list of averages over time

return np.array(averages)Trials and Error

Running this function once, I got an average of 5. A little lower than I expected, but not too far off. However, as any statistics major would quickly point out, one trial is not enough to draw a conclusion! We need to repeat this many times to see what is normal and what is not.

import numpy as np

def main():

# Number of games to run

n = 1000

# Simulate N games

stats = np.array([simple_sim()])

for index in xrange(n-1):

stats = np.concatenate((stats, np.array([simple_sim()])))

# Calculate statistics of those results

final_scores = stats[:, -1]

final_avg = np.average(final_scores)

final_stdev = np.std(final_scores)

print("Average final kill count: {}".format(final_avg))

print("Standard deviation: {}".format(final_stdev))Running this results in the following numbers:

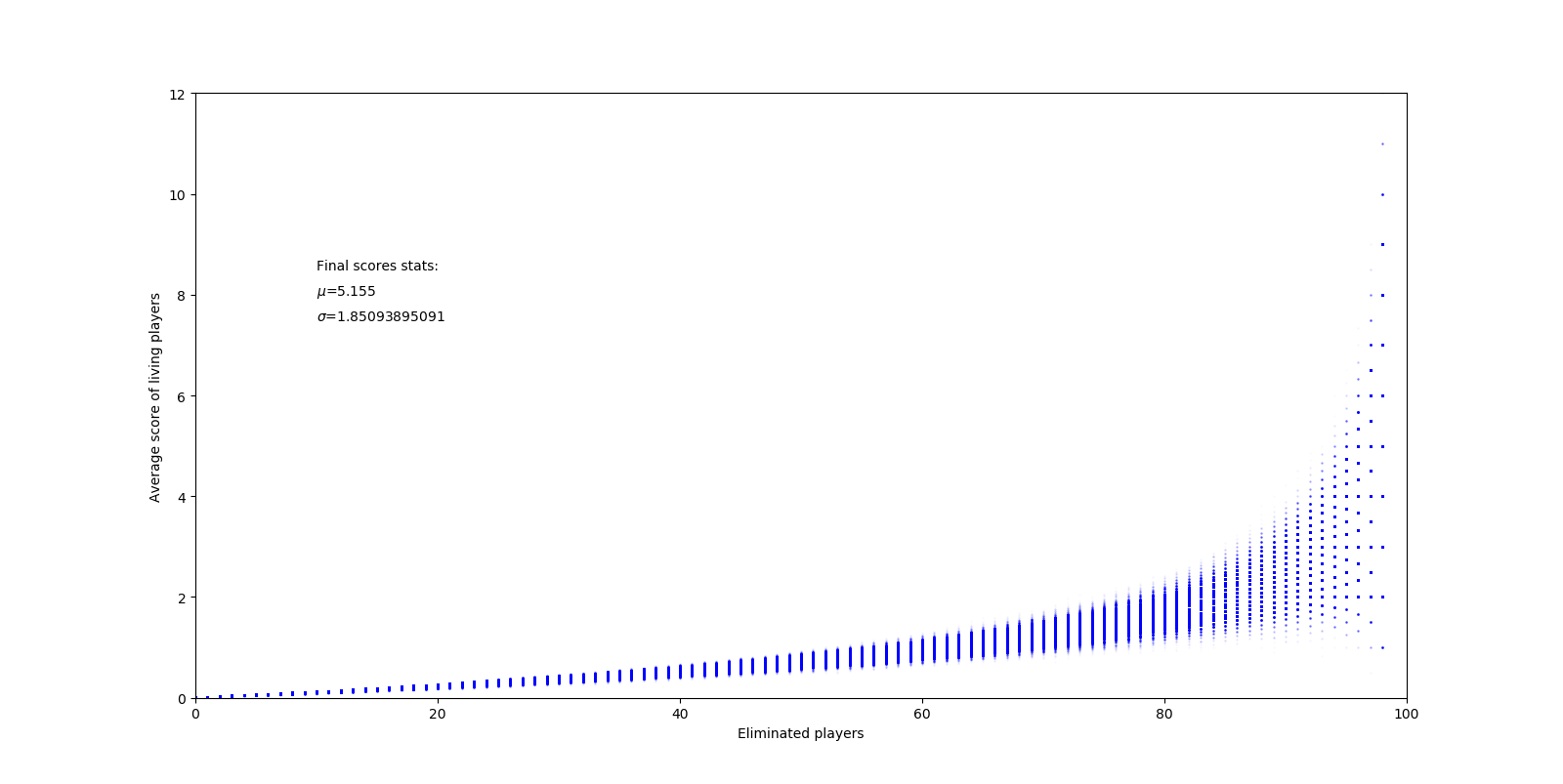

Average final kill count: 5.155

Standard deviation: 1.85093895091The Bigger Picture

Numbers are great, but a visualization would be even better. With matplotlib, we can generate a plot of every simulated game and the running averages for them:

def plot_averages(avgs, mu, stdev):

# Plot each simulated game separately

for index in xrange(len(avgs)):

pyplot.plot(avgs[index], 'bo', ms=1.0, alpha=0.01)

# Setup axis sizes

pyplot.axis([0, 100, 0, 12])

# Set axis labels and stat labels

pyplot.ylabel('Average score of living players')

pyplot.xlabel('Eliminated players')

pyplot.text(10, 8.5, 'Final scores stats:')

pyplot.text(10, 8, r'$\mu$={}'.format(mu))

pyplot.text(10, 7.5, r'$\sigma$={}'.format(stdev))

pyplot.show()The same test as earlier gives the following graph (right click to view full size):

Notice how each game starts off extremely consistently, then splinter off wildly toward the end. This is because of the randomness in the game – it’s entirely possible for players with low scores to take out high-scoring players, resulting in lower averages overall. This brings up another point – the simple simulation I created earlier assumes all players are of an equal skill level. While the game is good at matching up evenly-skilled players, it’s impossible to get 100 people of identical skill levels into a single game. So, how different would the graph look if we took variable skill levels into account? First, we need to modify the simulation function to include skill levels:

def complex_sim():

# Create an empty list to store averages over time

averages = list()

# Create list of integers representing players' score

players = np.zeros(100)

# Create a list of player's skills on a bell curve

skills = np.random.normal(10.0, 2.5, 100)

while len(players) > 1:

# Pick 2 different players at random

p1, p2 = np.random.choice(xrange(len(players)), size=2, replace=False)

pair_skills = skills[p1], skills[p2]

# Scale weights so they sum to 1

pair_skills = np.divide(pair_skills, sum(pair_skills))

# Pick winner of the pair randomly, using scaled skill levels as weights

# (So, higher skill is more likely to win)

winner = np.random.choice((p1, p2), p=pair_skills)

loser = p1 if winner == p2 else p2

# Increment winner's count, remove loser from players list

players[winner] += 1

players = np.delete(players, loser)

skills = np.delete(skills, loser)

# Add new average score to list

averages.append(np.average(players))

# Return the list of averages over time

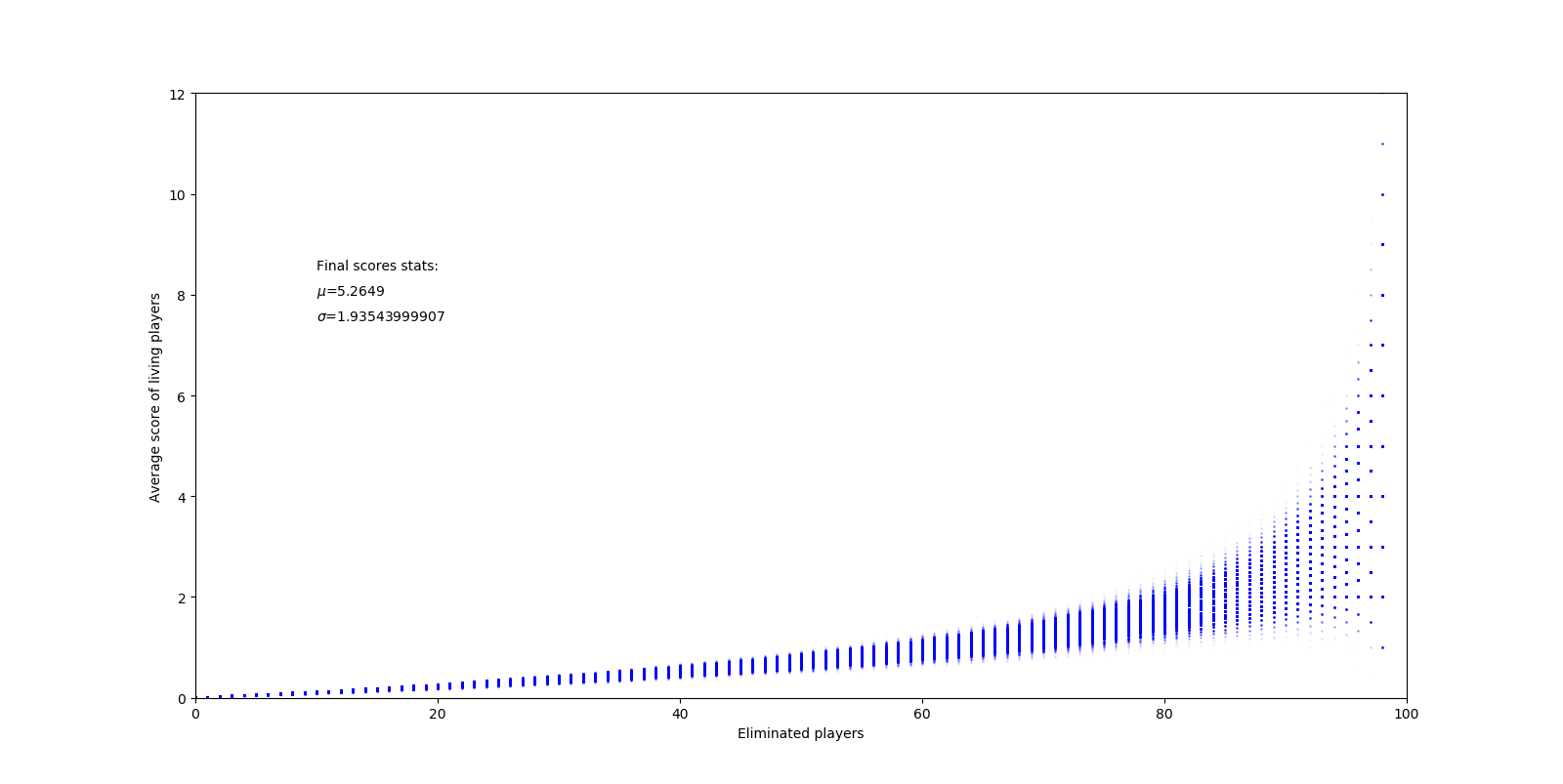

return np.array(averages)In this function, we assume the spread of skill levels is roughly a normal distribution, commonly seen as a bell curve. This means most players are around some average, with some better and some worse. With this new function, running 1000 games produces a plot like this:

Here, our overall average is a little higher. This is likely because eliminations are no longer completely random – higher skill players are more likely to eliminate low skill players, resulting in them getting higher scores and lasting longer.

Finally, let’s do one final test with a larger sample size. My computer couldn’t handle generating a plot with 500,000 matches, but it did give consistent numbers:

Average final kill count: 5.24504

Standard deviation: 1.91240461158Now, if you’re ever curious whether your score mid-game is good or not, there is a reference. Granted, if you’re still alive, then you’re probably doing better than me.